Geometry of Strength: Triangulated Structures

Triangulated structures are based on one of the simplest and most powerful geometric principles: the triangle is the only polygon that is inherently rigid. Unlike squares or rectangles, which can deform without changing the length of their sides, a triangle locks its angles once the side lengths are fixed. This simple fact is the reason triangulation has played a crucial role in building design for thousands of years—and why it remains essential today.

Historically, the understanding of triangular stability goes back to ancient civilizations. Early builders may not have described it mathematically, but they intuitively used triangular arrangements in roof frames, bracing systems, and stone construction. By the time of Ancient Greece, geometric principles were formally studied, and triangles became fundamental to structural reasoning. In medieval Europe, triangulated timber roof trusses allowed builders to span large spaces in churches, halls, and barns using relatively small amounts of material. These systems efficiently transferred loads to walls and supports while maintaining shape under gravity and wind.

The Industrial Revolution marked a major leap in the use of triangulation. With the rise of iron and steel, engineers began applying triangular frameworks to bridges, towers, and large-span structures. Famous bridge systems—such as Pratt, Howe, and Warren trusses—are all variations of triangulated frameworks. Their strength comes not from massive solid members, but from the way forces flow through interconnected triangles, placing elements primarily in tension or compression. This made structures lighter, stronger, and more economical.

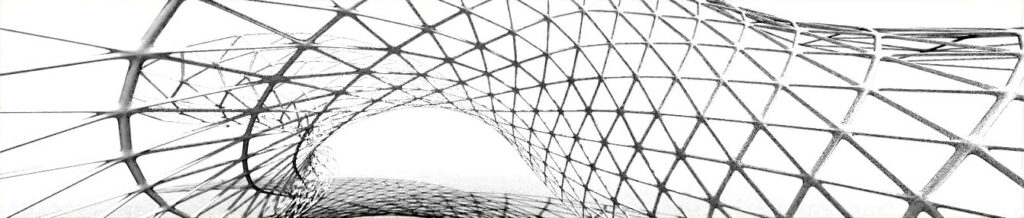

In the 20th century, triangulation found new expression through geodesic domes and spherical frameworks, popularized by Buckminster Fuller. These structures use networks of triangles distributed across curved surfaces, creating shells that are extremely stiff relative to their weight. Loads are spread evenly throughout the structure, reducing stress concentrations and allowing for large column-free interiors. Geodesic systems have been used for exhibition halls, planetariums, research stations, and lightweight enclosures in remote environments.

Today, triangulated systems are everywhere in building design, often in ways that are subtle or hidden. Steel space frames, timber gridshells, diagrids, and braced frames all rely on triangulation to resist gravity, wind, and seismic forces. In tall buildings, diagonal systems increase lateral stiffness, limiting sway and improving performance during earthquakes. In long-span roofs, triangulated frameworks allow designers to cover arenas, terminals, and industrial halls with minimal material while maintaining safety and durability.

The key property behind all these applications is stiffness. A triangulated structure resists deformation because changing its shape requires changing the length of its members, which takes significant energy. This geometric stiffness allows designers to control deflection, vibration, and overall stability without excessive mass. As materials, digital modeling, and fabrication methods continue to advance, triangulation remains a foundational strategy—proof that a simple shape, understood long ago, still defines how we build strong, efficient, and expressive structures today.

Historical and Contemporary Applications of Triangulation in Building Design

Gothic Cathedrals (Europe, 12th–16th c.):

-

Notre-Dame de Paris

-

Chartres Cathedral

- Cologne Cathedral

While not visually obvious, these buildings rely on triangulated load paths formed by ribbed vaults, flying buttresses, and roof trusses. Forces are redirected through diagonal elements, stabilizing tall stone walls and allowing unprecedented height and lightness for their time.

Significant Structures which use Triangulation as a base for theis structure:

Eiffel Tower — Paris, France (1889)

The Eiffel Tower represents one of the earliest and most explicit demonstrations of triangulation at a monumental scale. Its entire iron framework functions as a three-dimensional truss, composed of thousands of straight members connected to form rigid triangular units. This geometric configuration allows the structure to efficiently resist wind loads and self-weight through stiffness generated by form rather than by excessive material mass.

Forth Bridge — Scotland (1890)

The Forth Bridge is a massive steel cantilever railway bridge that illustrates the effectiveness of large-scale triangulated truss systems. Its structural logic demonstrates how triangular configurations can simultaneously manage compression and tension forces over extreme spans, enabling a level of durability and stability that would be difficult to achieve using non-triangulated forms.

Shukhov Hyperboloid Water Tower — Nizhny Novgorod, Russia (1896)

The Shukhov Tower is formed entirely from straight steel members arranged in diagonal, intersecting grids. Although the overall form is curved, the structure is composed of linear elements that create a continuous network of triangles. This triangulated hyperboloid system provides exceptional stiffness and stability while using remarkably little material, showcasing the efficiency of geometry-driven design.

Golden Gate Bridge — USA (1937)

While primarily known as a suspension bridge, the Golden Gate Bridge relies heavily on triangulation for its structural stability. Beneath the roadway, a fully triangulated stiffening truss plays a critical role in resisting wind-induced vibrations and dynamic loads, ensuring the overall performance and longevity of the structure.

Skylon — London, UK (1951)

Built for the Festival of Britain, the Skylon appeared to float above the ground, yet its stability was achieved through triangulated cable systems. These cables formed a geometric tension network that provided stiffness through prestressing rather than mass. The project stands as an early example of triangulation applied within tension-based systems, expanding the concept beyond traditional compression structures.

Kobe Port Tower — Kobe, Japan (1963)

The Kobe Port Tower is a clear example of an explicit hyperboloid lattice structure in post-war architecture. Its inclined, intersecting members form a triangulated network that stabilizes the tower while creating a visually expressive form. The project demonstrates how triangulation and hyperboloid geometry can be combined to achieve both structural efficiency and architectural identity.

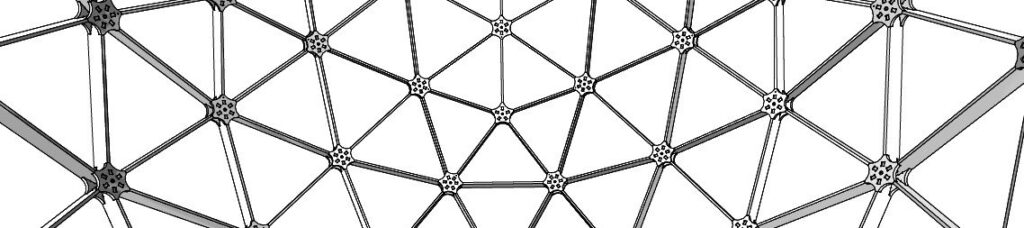

Montreal Biosphère — Montreal, Canada (1967)

Designed by Buckminster Fuller, the Montreal Biosphère is a classic geodesic sphere composed of a dense triangular network. This configuration distributes loads evenly across the structure, resulting in an extremely high strength-to-weight ratio. The project exemplifies how triangulation can generate lightweight yet robust enclosures at large scales.

John Hancock Center — Chicago, USA (1970)

The John Hancock Center employs an exterior X-bracing system that transforms the entire building into a giant vertical truss. By using diagonal members on the façade, the structure achieves high stiffness against wind loads while reducing the amount of material required. This approach allowed for greater structural efficiency and flexible interior layouts.

Sydney Tower (Sydney Tower Eye) — Sydney, Australia (1981)

Sydney Tower applies hyperboloid structural logic through inclined, intersecting elements rather than a purely vertical shaft. The observation deck is supported by a prestressed system in which geometry and tension work together to balance vertical and horizontal forces. This project represents a late twentieth-century continuation of hyperboloid theory, adapted to concrete and prestressed construction techniques.

Louvre Pyramid — Paris, France (1989)

The Louvre Pyramid is a steel-and-glass space frame in which every panel participates in a triangulated structural system. This configuration enables high transparency while maintaining sufficient stiffness and stability. The project demonstrates how triangulation can support architectural lightness and visual clarity without compromising structural performance.

Eden Project Biomes — Cornwall, UK (2001)

The Eden Project Biomes represent a modern evolution of geodesic principles. Although their visible pattern consists primarily of hexagonal and pentagonal panels, the underlying steel space frame relies on triangulated connections at the nodes. Structurally, the system behaves more like a polygonal shell or space frame than a lattice of explicit triangles, yet triangulation remains fundamental to its performance.

30 St Mary Axe (The Gherkin) — London, UK (2003)

The Gherkin is wrapped in a diagonal steel grid that provides structural stiffness and torsional resistance. This triangulated system allows the building to withstand wind loads efficiently while enabling open, column-free interior spaces. The project illustrates how triangulation can be integrated seamlessly into contemporary high-rise form.

Hearst Tower — New York City, USA (2006)

The Hearst Tower uses a diagrid structural system in which triangulation replaces many conventional vertical columns. This approach significantly reduces steel usage while maintaining high structural performance. The building demonstrates the material efficiency and clarity that triangulated systems can offer in modern skyscraper design.

Beijing National Stadium (Bird’s Nest) — Beijing, China (2008)

Despite its seemingly irregular appearance, the Beijing National Stadium relies on interconnected diagonal members that form triangulated load paths. These triangulated systems stabilize the massive outer shell and distribute forces efficiently throughout the structure. The project shows how triangulation can underlie even the most expressive and unconventional architectural forms.

From stone cathedrals to steel bridges and glass towers, triangulation is one of the most universal and enduring tools in building design—and many of the world’s most iconic structures owe their existence to it.

These remarkable inventions and structural examples are a tremendous source of inspiration for the FANCY STRUCTURE Team. They encourage us to explore, experiment, and push the boundaries of design, motivating us to create innovative structures that combine efficiency, strength, and elegance. Studying these pioneering solutions fuels our curiosity and drives us to apply the same principles of geometry, triangulation, and material efficiency in our own work.